Resistance at the Dique do Tororro

GSAPP Advanced Studio

Instructor: Mario Gooden

Spring 2018

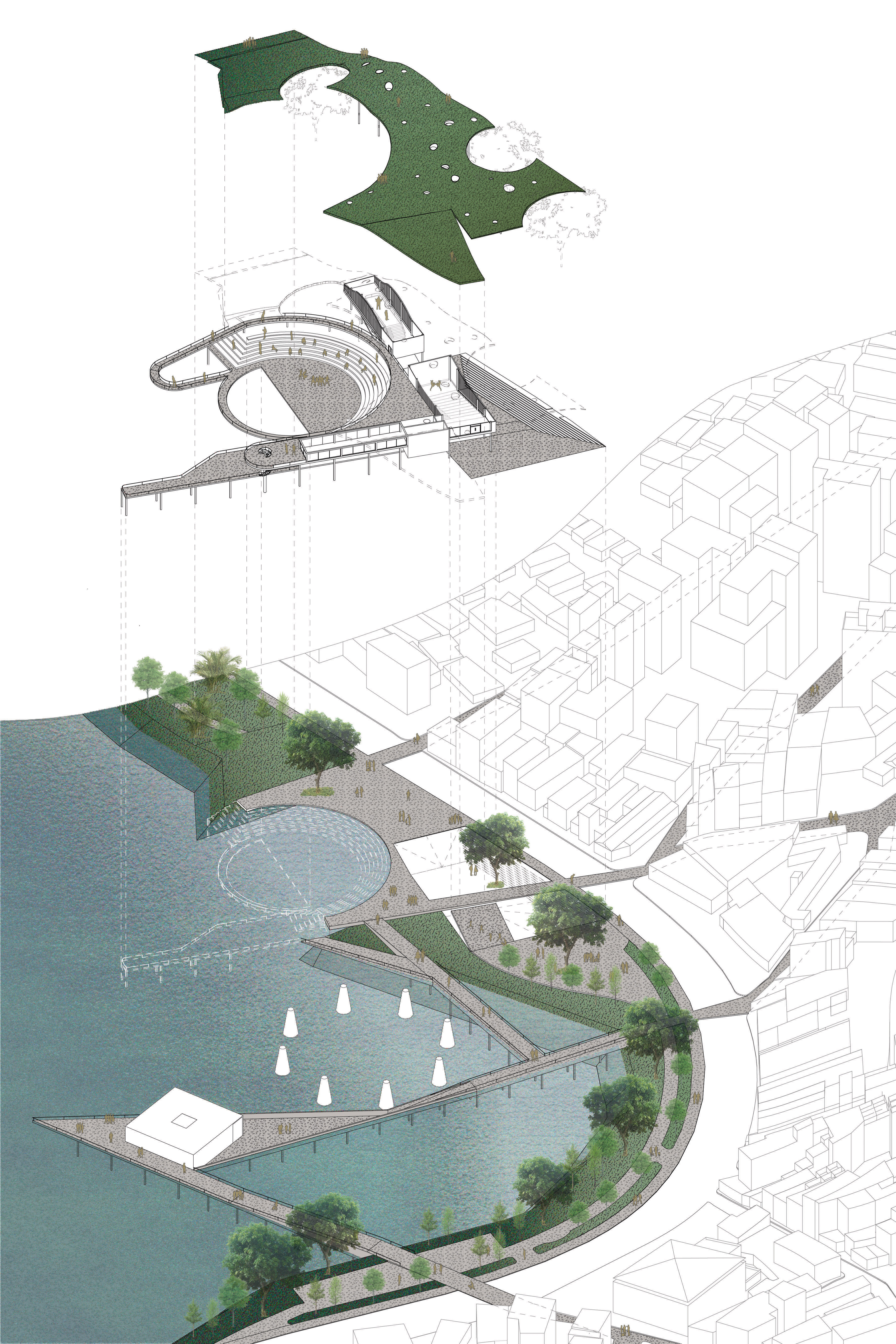

This project explores the tensions triggered by the growing tourism in Salvador, Bahia through the appropriation of the cultural and religious symbols of Afro-Brazilian communities. By confronting the representations that appropriate sacred spaces of Candomble, the project aims to reclaim and establish subjectivity through the introduction of spaces of expression that celebrate Afro-Brazilian identities.

To unpack these tensions, the project focuses on the Dique do Tororo, a lake historically considered as sacred withinin the religion of Candomble. This sacredness arises from the reverence of natural elements in Candomble, since the lake is the only natural spring in Salvador, Bahia. In 1998, the site went through a revitalisation project featuring an installation of eight Orixa statues by the artist Tati Moreno representing the deities of Candomble, weighing 2 tons each and are more than 22 feet tall. However, this “revitalisation” of the site became an isolator of the lake from the neighborhoods surrounding and the busy avenues newly developed brought in a lot of traffic. The lake and the statues, then, become unattainable to the those living in the neighborhoods surrounding it, instigating a tension in-between.

The project tackles these issues by strengthening the connection of the lake with the neighborhood in an attempt to reclaim a site that represents cultural and religious freedom to Afro-Brazilians. Thus, the existence of architectural representation of a group in a space becomes equal to a sense of belonging, of one’s place within an urban fabric.

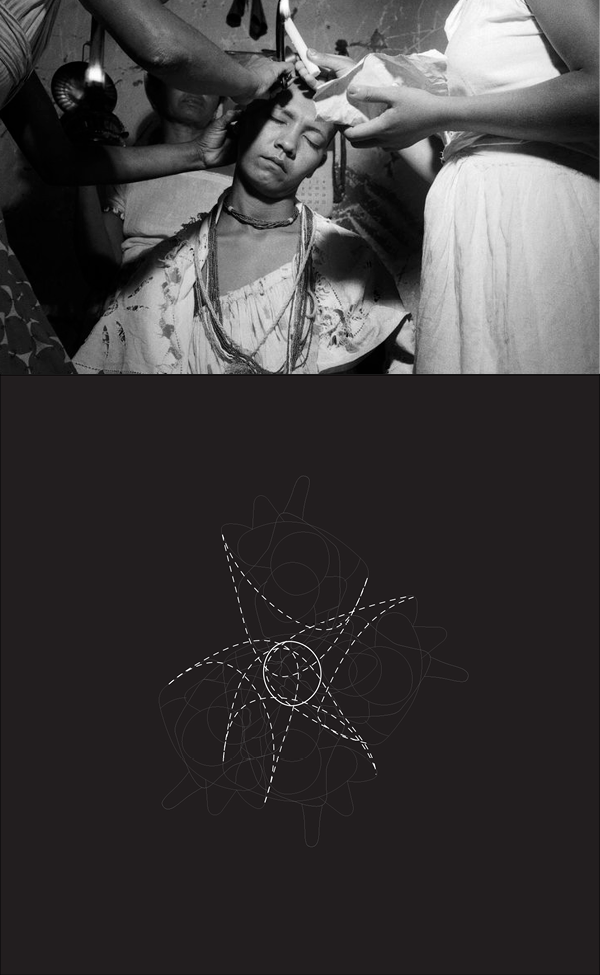

Analysis for Two-Person Parangolé Experiment

The concept of tension was explored by taking Oiticica’s Parangolé as a case study. The Parangolé designed by Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica is an object that could be made out of flags, tents, and capes, painted or printed fabrics that are meant to be used by the viewer. The artwork is activated when one wears it and dances to samba. Oiticica described the experience of the individual- at once private and collective, intimate and spectacular- as the ciclo “vestir-assistir” (wearing- watching cycle). I argue that this experience could be enhanced in that the watching and wearing could be paired together to become one and the same.

My take on the Parangolé is to push forward the idea of the collective experience by allowing the Parangolé to encompass more than one body at a time. I conducted an experiment with two dancers wearing a paired Parangolé that connected both the dancers but still allowed for individual spaces of expression. This reenvisioned Parangolé automatically generated a void between the dancers and the Parangolé itself. This Void was put in tension continuously through the proximity of the dancers to each other and their movement. The Parangolé in this context transformed into a tool that allows for power negotiations between the dancers; when one of them moves the other is forced to respond because of the pairing.

The concept of tension was explored by taking Oiticica’s Parangolé as a case study. The Parangolé designed by Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica is an object that could be made out of flags, tents, and capes, painted or printed fabrics that are meant to be used by the viewer. The artwork is activated when one wears it and dances to samba. Oiticica described the experience of the individual- at once private and collective, intimate and spectacular- as the ciclo “vestir-assistir” (wearing- watching cycle). I argue that this experience could be enhanced in that the watching and wearing could be paired together to become one and the same.

My take on the Parangolé is to push forward the idea of the collective experience by allowing the Parangolé to encompass more than one body at a time. I conducted an experiment with two dancers wearing a paired Parangolé that connected both the dancers but still allowed for individual spaces of expression. This reenvisioned Parangolé automatically generated a void between the dancers and the Parangolé itself. This Void was put in tension continuously through the proximity of the dancers to each other and their movement. The Parangolé in this context transformed into a tool that allows for power negotiations between the dancers; when one of them moves the other is forced to respond because of the pairing.

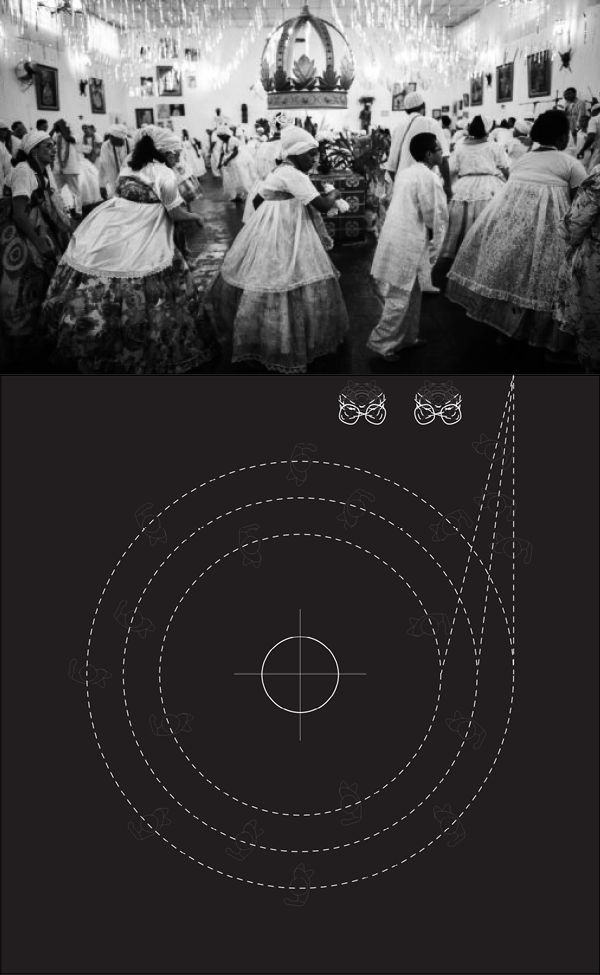

Diagram of a Candomble Ceremony displaying Orixas (Deities) and other participants

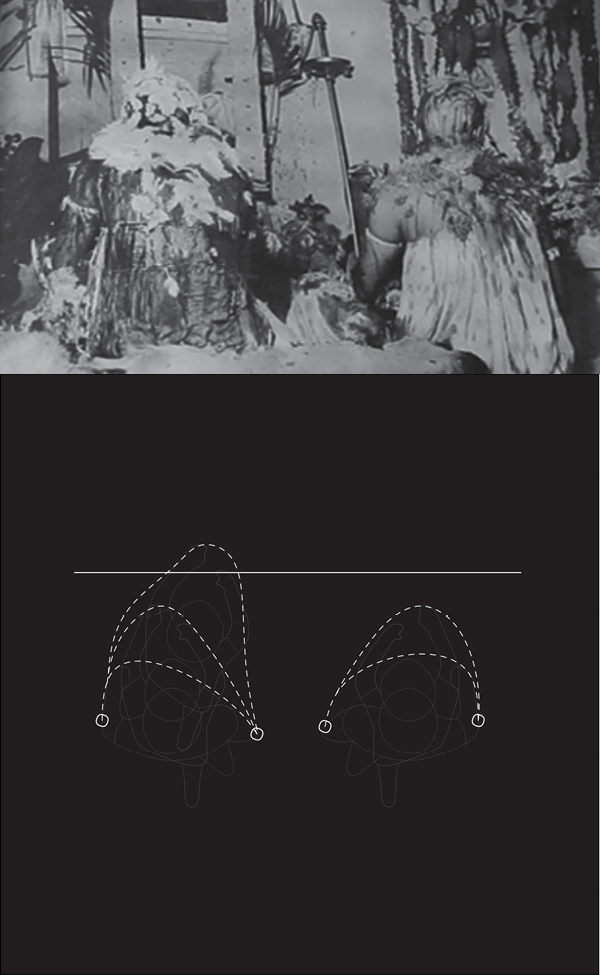

The religion of Candomble developed in a creolization of traditional Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu beliefs brought from West Africa by enslaved captives in the Portuguese Empire. The religion developed in Brazil, influenced by the knowledge of enslaved African priests who continued to teach their mythology, culture, and language. Candomble translates to “dance in honour of the Gods”, centering music and dance as important components of the religion. In this sense, Candomble acts as a preserver of Africanness in Brazil and is a generator of Afro-Brazilian Culture.

The religion of Candomble developed in a creolization of traditional Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu beliefs brought from West Africa by enslaved captives in the Portuguese Empire. The religion developed in Brazil, influenced by the knowledge of enslaved African priests who continued to teach their mythology, culture, and language. Candomble translates to “dance in honour of the Gods”, centering music and dance as important components of the religion. In this sense, Candomble acts as a preserver of Africanness in Brazil and is a generator of Afro-Brazilian Culture.

During it’s early history, the state of Bahia repressed the practice of Candomble by outlawing ceremonies, confiscating sacred objects and ordering the arrest of individuals who were caught in possession of its material culture. In order to escape religious persecution, Candomble Terreiros were driven underground, becoming hidden spaces within the urban fabric. Practicing Candomble became legal in the 1970s through a shift in it’s public image after its practitioner’s made significant efforts to open up to Brazilian society. Today, Bahia identifies as “Africa of Brazil” and takes pride in its African heritage, however, Bahians of African descent continue to suffer from racial discrimination in the private and public sectors.

Map of Candomble Terreiros of Salvador

The Dique do Tororo has traditionally served as a natural altar site sometimes used for the safe disposal of powerful objects. A mapping of the locations of Terreiros in Salvador reveals the important role that the lake has played within Afro-Brazilian communities and it’s relationship to the religon. After the Orixa installation project by Moreno, the site was no longer private enough to allow spiritual reflection and the volume of offerings decreased drastically following the revitalisation project.

Dique do Tororo 1: Laundress by the Lake

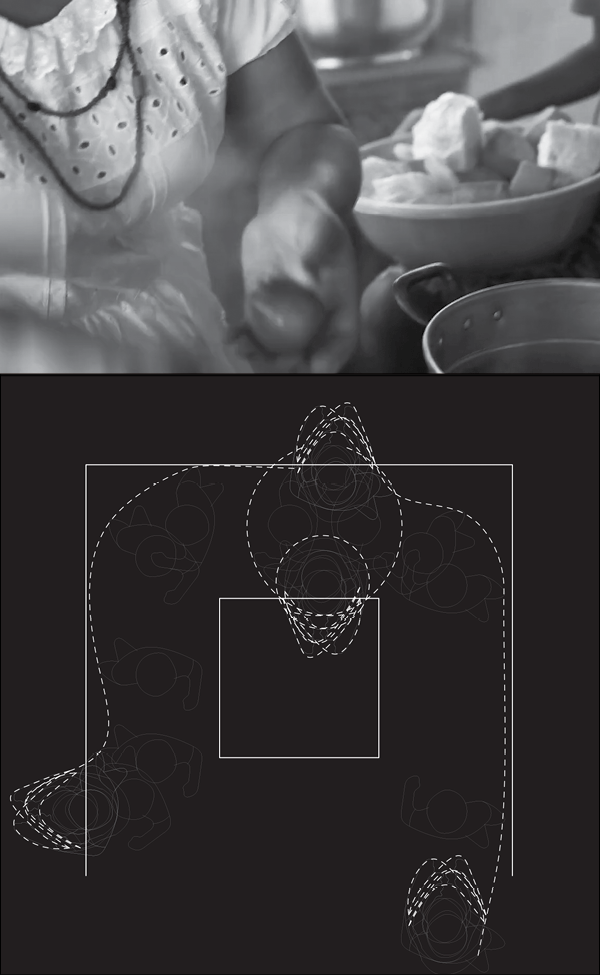

Food 1: Preparation

Food 1: Preparation

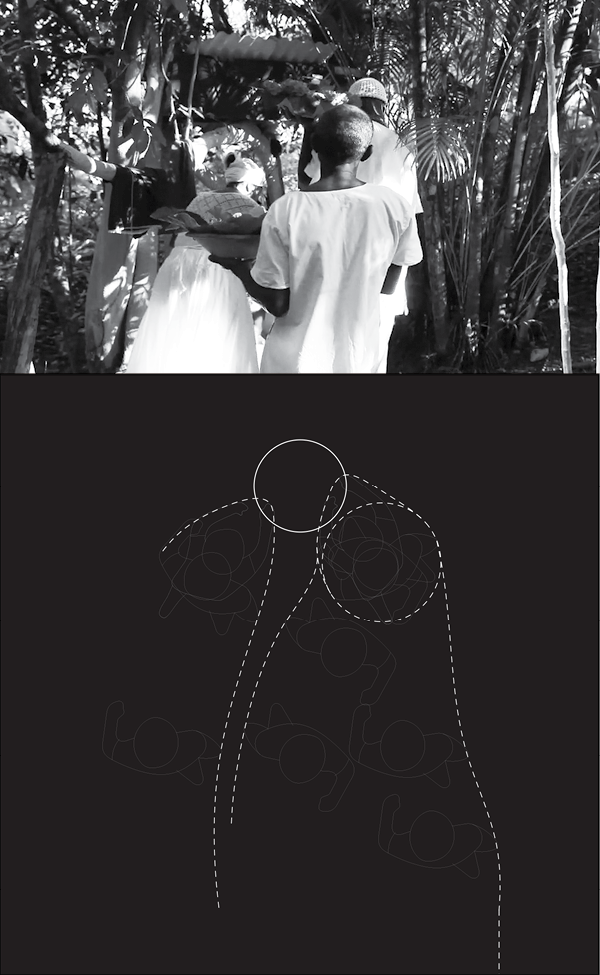

Food 2: Offering in the woods

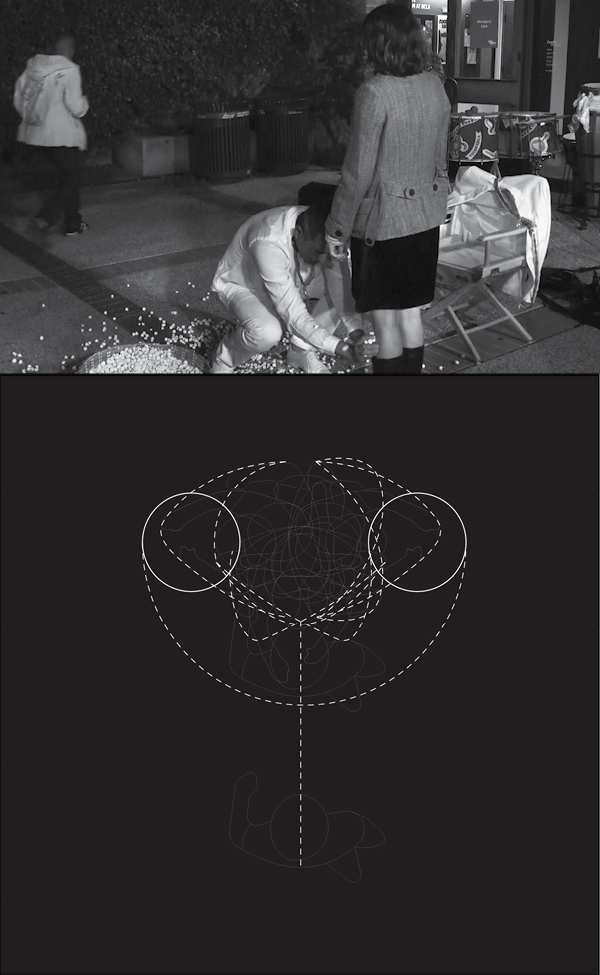

Cleansing and Blessing

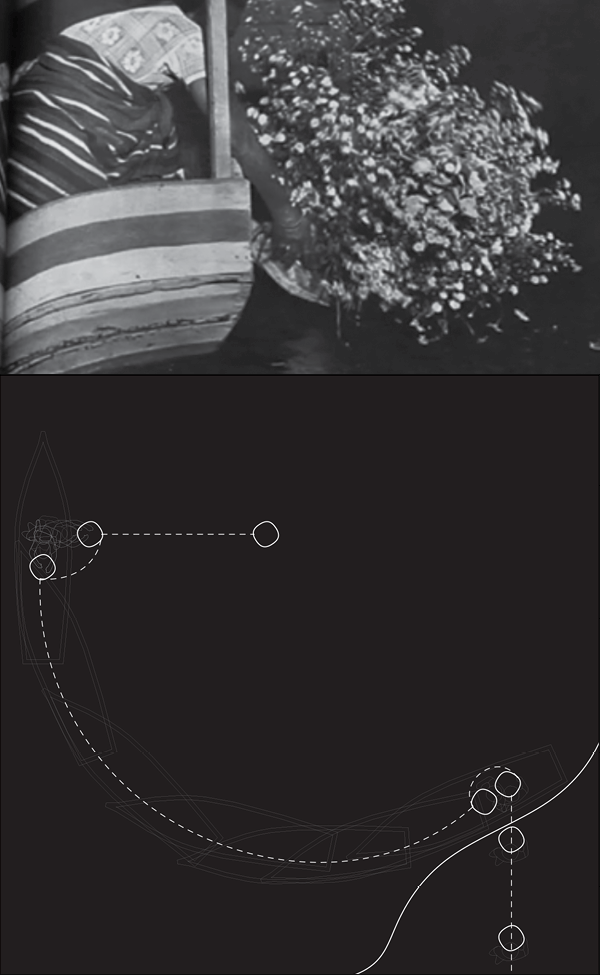

Dique do Tororo 2: Lake Offering

Initiation 1: God of My Head

Initiation 2: Altar

Ceremony

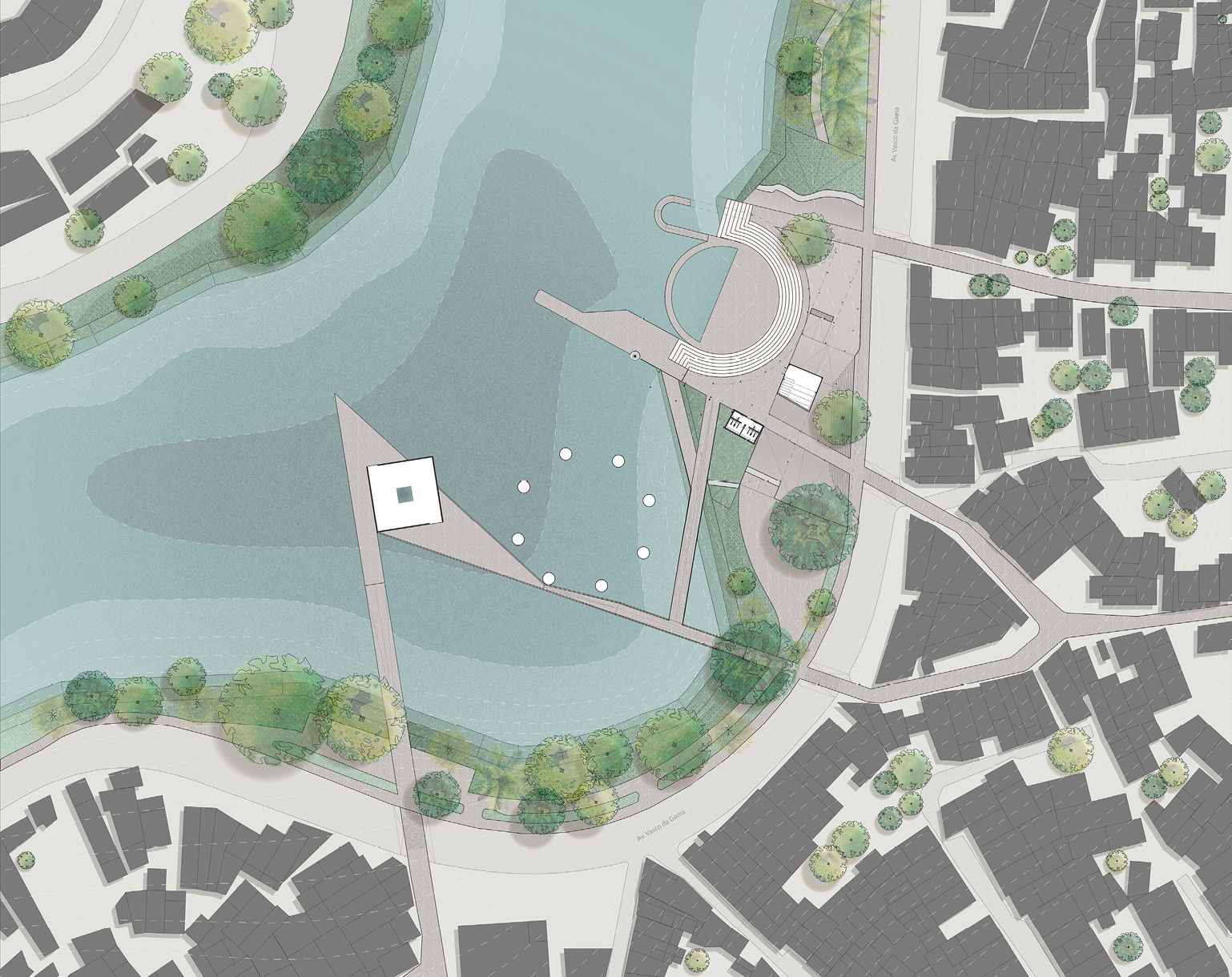

The avenue Vasco da Gama that surrounds the lake from the east bank acts as a divider between the low-income communities living in the Engenho Velho de Brotas neighbourhood and the linear park currently on the river bank. The speed of the cars passing through the avenue enforces this divide and renders the lake difficult to approach.

The project aims to transform the relationship of the neighbourhood with the park by allowing the neighbourhood to easily flow into the park and enlarging the park from a mere corridor into becoming a community space.

Ground Floor Plan

Ground Floor Plan

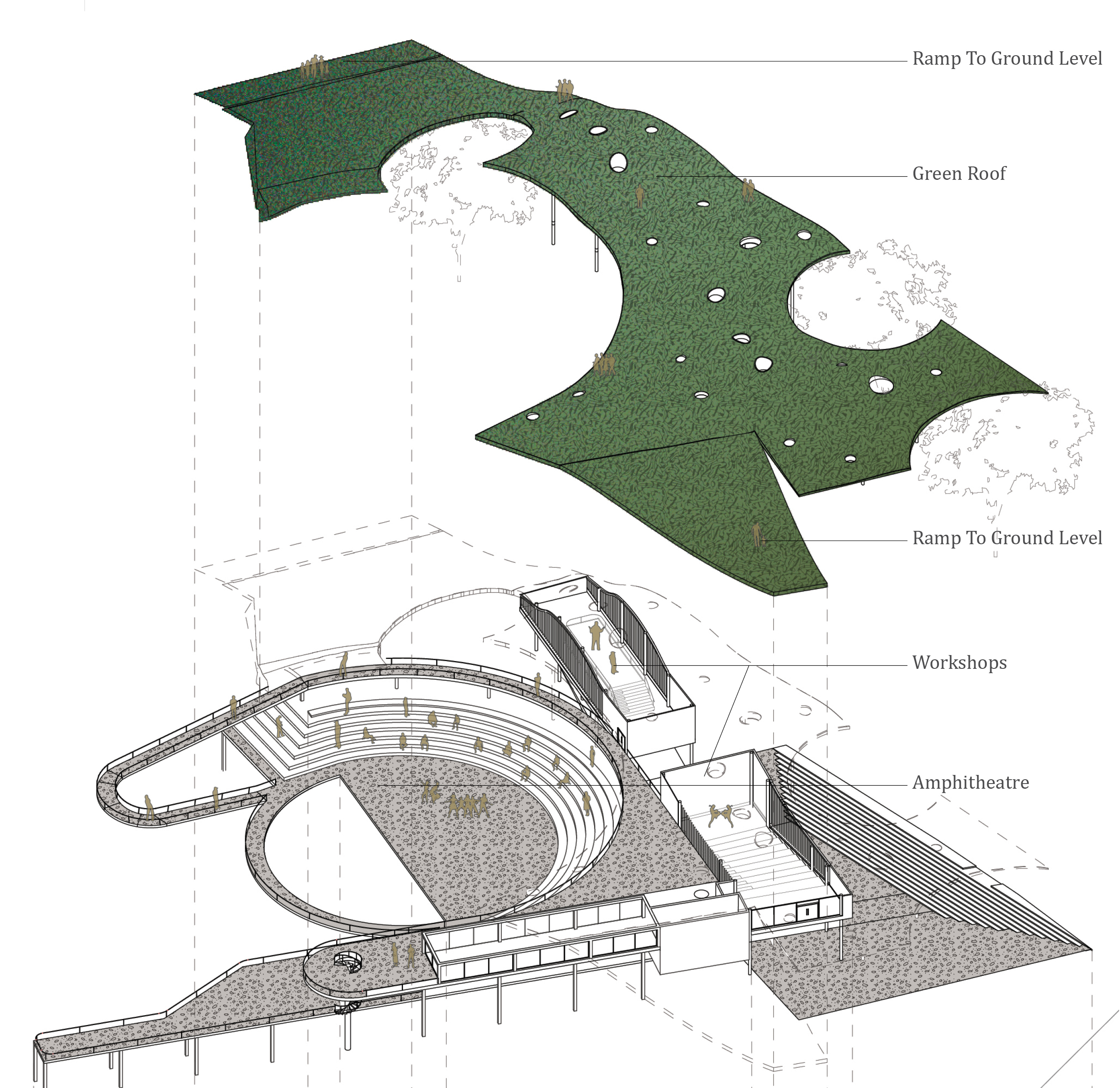

By creating a series of gathering spaces that enable the community to occupy the site, the project reverses the current isolation of the lake from the neighborhood. The park acts as a continuous surface that allows pedestrians to walk from the ground level to the roof that covers the workshops.

The pathway extending from the park to the lake offers another experience to Moreno’s eight Orixa statues installation. The pathway is a transition from the recreational and collective community space of the park to the individual contemplative space that allows the community to occupy the lake.

Today, the placement of the Orixa statues in the lake creates an in-between state where people can see the statues but cannot engage with them. The project challenges the unattainability of the statues and allows people to experience this installation from multiple perspectives until finally reaching a contemplation zone that allows reflection.

The workshops are dedicated to the cultural practices specific to Afro-Brazilians such as Dance, Music and Capoeira. By creating spaces of learning and practice, the project creates a dialogue between the representations of the Orixa statues with the cultural practices of Afro-Brazilians.

Sections Across Workshops

Sections Across Workshops

Sections Across Workshops